Postcards from the Revolution

Die Ausstellung ‹Feminist Lessons› im Foyer des HIL-Gebäudes der ETH Hönggerberg schliesst morgen seine Tore. Sie ist einen (kurzfristigen) Besuch wert, wie Hamish Lonergan in seiner Rezension schreibt. [Engl.]

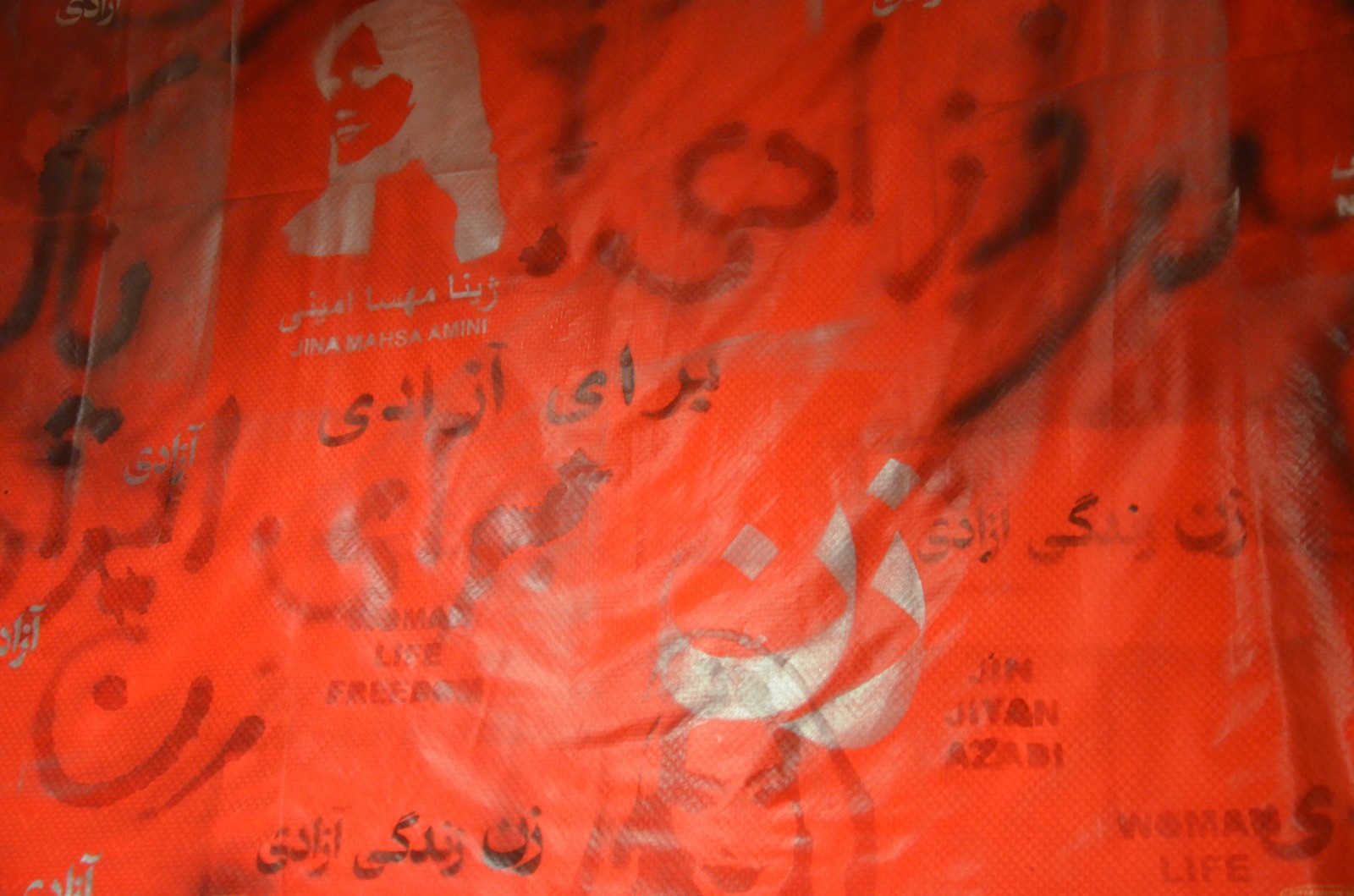

At the centre of the exhibition ‹Feminist Lessons from a Feminist Uprising in Iran› is a tapestry woven with slogans chanted in the woman-lead protests sweeping Iran: «Woman, Life, Freedom» only the most well-known. It is festooned with the names of those imprisoned and killed by the regime since Mahsa Amini died in morality police custody on 16 September, compelling millions of Iranians to the streets. They have not left since.

This tapestry hangs from the ceiling of the HIL building foyer at ETH Hönggerberg, floating just below head height. As a well-behaved exhibition-goer, I’ve been conditioned to avoid touching such articles at all costs. So, when I felt the cloth brush my forehead—too engrossed in these slogans streaking, graffiti-style, over its surface to notice our immanent collision—I performed an evasive manoeuvre.

I ducked. Then turned around, sheepishly, to see if anyone saw me move so clumsily. Ducking, turning, I noticed details that I’d missed before. My focus shifted, involuntarily, from those faces to the golden logo of the Austrian fabric manufacturer Getzner printed along the hem. It was one of those moments that breaks the fourth wall of an exhibition, revealing the way the tapestry had been painstakingly assembled in Zurich from fragments of a revolution half a world away. The curators showed me the pile of discarded stencils, copied from photos smuggled out Iran, mimicking the images of Amini and others that have appeared on walls across the country.

This is a subtle, deeply moving exhibition. It also expects us on our toes: to duck. It is not the frictionless gallery experience that we have come to expect from many architecture shows, with serene photographs and plinthed models. My passage through it was not always straightforward: its lessons not always explicit. Instead of undemanding consumption, it asks us to bring our own experiences, and bodies, to bear in interpreting it. But, in return, the reward are shifts in perspective—on the uprising, and the relationship between Iran and architecture more broadly—not unlike the sudden change in vantage point when I ducked.

The curators write in their essay that this is an exhibition about walls—physical and metaphoric, fabric veils and concrete barriers—that have subjugated Iranian women: that are in the process of being torn down. Walls, they write with quiet poetry in the exhibition essay, that «are all scratched up by women living behind them…muting their voices…the other side of this story is the story of the radical transgression and uprising of those, in the words of Audre Lorde, ‹who never meant to survive›.»

The exhibition itself comprises three walls. In the middle is the tapestry. Parallel, a wall painted red with two archival display cases of books and records at its base. Between them the curators have laid a bouquet of flowers, turning this red wall into a memorial to the blood shed, and lives lost, in the uprising so far.

This red wall bears a frieze of postcards, overlaying scenes from the protests onto older Iranian artworks: a portrait of Ali Khamenei burning on a scaffolding superimposed on a Persian miniature; in another, a veiled woman paints «death to Khamenei» on the ground. I was drawn to an aerial photograph of steel workers on strike, their helmets bright blue dots against a geometric pattern—taken, perhaps, from a rug or mural—with a repeated motif resembling a plant’s stamen (or a clitoris). These patterns are echoed below, where the funerary bouquet has been doubled in a mirror placed behind. In these superimpositions, the images of protests and mourning become strikingly beautiful, all the more so for capturing moments in the midst of violence, and emancipation.

On the third wall, a projector beams in videos of the uprising. Some of these are familiar, picked up by European news outlets, such as the trio of primary school girls whipping off their headscarves and chanting «Woman, Life, Freedom». Others, often from social media, are not. Women in full chador spray-paint anti-regime graffiti across a wall mural, transformed into a billboard for liberation. One after another, the clips underscore how widely these protests have been embraced by women, veiled or not, capturing the moments of intense joy as well as tragedy. They remind me, too, of the virtual walls that separate me from the women risking everything for change inside Iran: the algorithms that send me memes instead of these dispatches from the revolution.

What should we as visitors make of these assembled objects and images, across these three walls? As I wander the space, the fragments seem to oscillate, beginning to vibrate against each other as they recompose themselves in different configurations of meaning. Making sense of their connections requires something from us as viewers: whether or not to duck is up to us.

A postcard of Khamenei made up in drag chimes with a book in the archival case below, Afsaneh Najmabadi’s Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (2005). Someone has highlighted a line on an open page of Farzaneh Milani’s Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women Writers (1992): “Like walls that enclose houses and separate inner and outer spaces, the veil makes a clear statement about the disjunction between the private and public.” Held in tension, they hint at the way gendered constructions encircle both men and women in a walled, veiled society.

We could follow this thread to a record cover of the singer Googoosh from the 1980s—looking like an international diva in her unveiled bob—contemporaneous with the Azadi Tower, shown here, moodily-lit in another open book, it was the only Iranian building that made it into my architectural history course at university. It is tempting to read them together: that the modern, pre-revolutionary society that commissioned this architectural icon and worshipped Googoosh was uniformly good for women. But, as the exhibition reminds us, this is too easy. A spread from Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Persepolis depicts women taking to the streets for the right to wear the veil—following the Shah’s forced unveiling in 1936—just as other women fought to walk bare-headed. Both pre- and post-revolutionary governments imposed walls on women’s bodies.

It might strike some visitors strange that the Azadi Tower is the only work of architecture in an exhibition hosted in an architectural school. Instead, this is quite deliberate. The postcards, with their backgrounds from classical Iranian art and wall decoration, force us to question the aesthetic hierarchies that lead us to value these works, or canonical buildings, over anonymous graffiti—applied to walls with care not unlike older murals—or the protest artworks made by university students across the country. The confrontation of these images is a stark reminder of the simplifying, Orientalising impulse which sees architectural history teach us about static buildings and richly geometric Iranian interiors while often neglecting the complex social and material forces at play in their creation: the forces that are on full display in the artworks erupting out of these protests.

The curators tell me that the exhibition is partly a reaction to the way architects often view world events through the lens of architecture: reducing disasters and tragedies to design problems. There is something darkly comic, then, in the word «Lessons» in the exhibition’s title, with so few prepacked teachings for architects on show.

This does not mean, however, that a spatial sensibility is missing from their exhibition. At first, I had been irked by its arrangement: the projector wall separated by the entryway from tapestry and memorial, themselves positioned in the anteroom between the gta Exhibitions gallery and the Alumni Lounge café. I wondered why it had not been given a more prominent, less provisional, position in the building: whether this reflected the priorities of the school. Yet, as the curators tell me, the opposite is true. ‹Feminist Lessons› slipped into the gaps between an exhibition schedule planned months in advance, responding, almost in real time, to the events in Iran.

And from these interstitial spaces, the curators have crafted something with real intimacy, inviting passersby to linger. In ducking under it, the tapestry creates a threshold, carving a zone from the busy foyer to contemplate the postcards, the archival cases, the funerary bouquet, the sounds from projected clips mingling with the sounds of students walking by. There is an uncanniness here, of seeing world-changing events from afar in a quotidian school context. Placed in the busy foyer, many more people might be confronted with these voices from Iran, than would take the time to visit it in a gallery out of the way.

This is an exhibition with no easy narratives; after all, there can be few certainties in an archive to an ongoing revolution. The constellations visitors chart between its fragments, images, books, films will be different to the those I write about here. You might not even have to duck (I am unusually tall). ‹Feminist Lessons› is so compelling because the curators have made space for these interpretations, while providing enough hints to guide us through.

It’s only after I leave ‹Feminist Lessons›, that I realise how many of the image and film captions mention the anonymity of the figures depicted. This repetition is a striking: a stark contrast to the authored works by canonical—often male—figures we normally see in architectural exhibitions; and a reminder that without anonymity, these protesters risk imprisonment and execution at the hands of religious authority. It is only later that it occurs to me that some of the only names are those of the curators Alexander Cyrus Poulikakos and Niloofar Rasooli, with contributions by Qianer Zhu, Elisaveta Kriman and Deniz Örün, and the participants of the roundtable discussions on opening night: Bilgin Ayata, Sanaz Azimpour, Dastan Jasim and Elli Mosayebi. I name them here in recognition that curating an exhibition like this—in support of the uprising, against religious and even architectural regimes of power, risking exile from Iran until its supreme leader falls—is an act of rebellion too.

* Hamish Lonergan ist Architekt und Doktorand am gta Institut der ETH Zürich.

Feminist Lessons from a Feminist Uprising in Iran

Veranstalter: gta Ausstellungen

Datum: bis Freitag, 27. Januar 2023

Mehr Info